Elevated preoperative plasma D-dimer dose not adversely affect survival of gastric cancer after gastrectomy with curative intent: A propensity score analysis

Introduction

A systemic hypercoagulable state is frequently observed in patients with advanced-stage tumor, even in the absence of thrombosis (1,2). D-dimer, which is produced when cross-linked fibrin was degraded in fibrinolytic activity, can reflect enhanced fibrin formation and fibrinolysis hypercoagulability. It is reported that D-dimer can not only affect cellular signaling systems and promote cell proliferation, but also stimulate the cellular adhesion of tumor cells to endothelial cells, affect platelets and extra-cellular matrix, and ultimately, induce the growth and spread of tumors (3,4). Many studies have affirmed that high levels of plasma D-dimer were associated with advanced tumor stage and poor survival of cancer patients (5-12). Several researches reported that preoperative plasma D-dimer level (PDL) was an independent prognostic factor in patients with completely resected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (5-7), and others confirmed that the prognosis was significantly influenced by the elevated PDL in patients with colorectal cancer (8-10), esophageal cancer (11), breast cancer (12) and so on. As for gastric cancer (GC), few studies focus on plasma D-dimer. Liu et al. demonstrated that PDL was a valuable biomarker for peritoneal dissemination and GC patients with high PDL had a poor prognosis (13). As the level of plasma D-dimer was correlated with tumor stage, tumor size and other prognostic factors as previous studies reported (2,13-15), therefore, it was vital important to adjust for imbalances regarding baseline characteristics between patients with elevated PDL and those with normal PDL, especially in retrospective analysis. In this study, we used both Cox proportional hazard regression analysis and propensity score method to overcome bias due to different distribution of covariates for the groups. Our ultimate aim was to evaluate the potential impact of PDL on the long-term outcome of GC patients after curative surgery in a single high-volume center in China.

Materials and methods

Patients

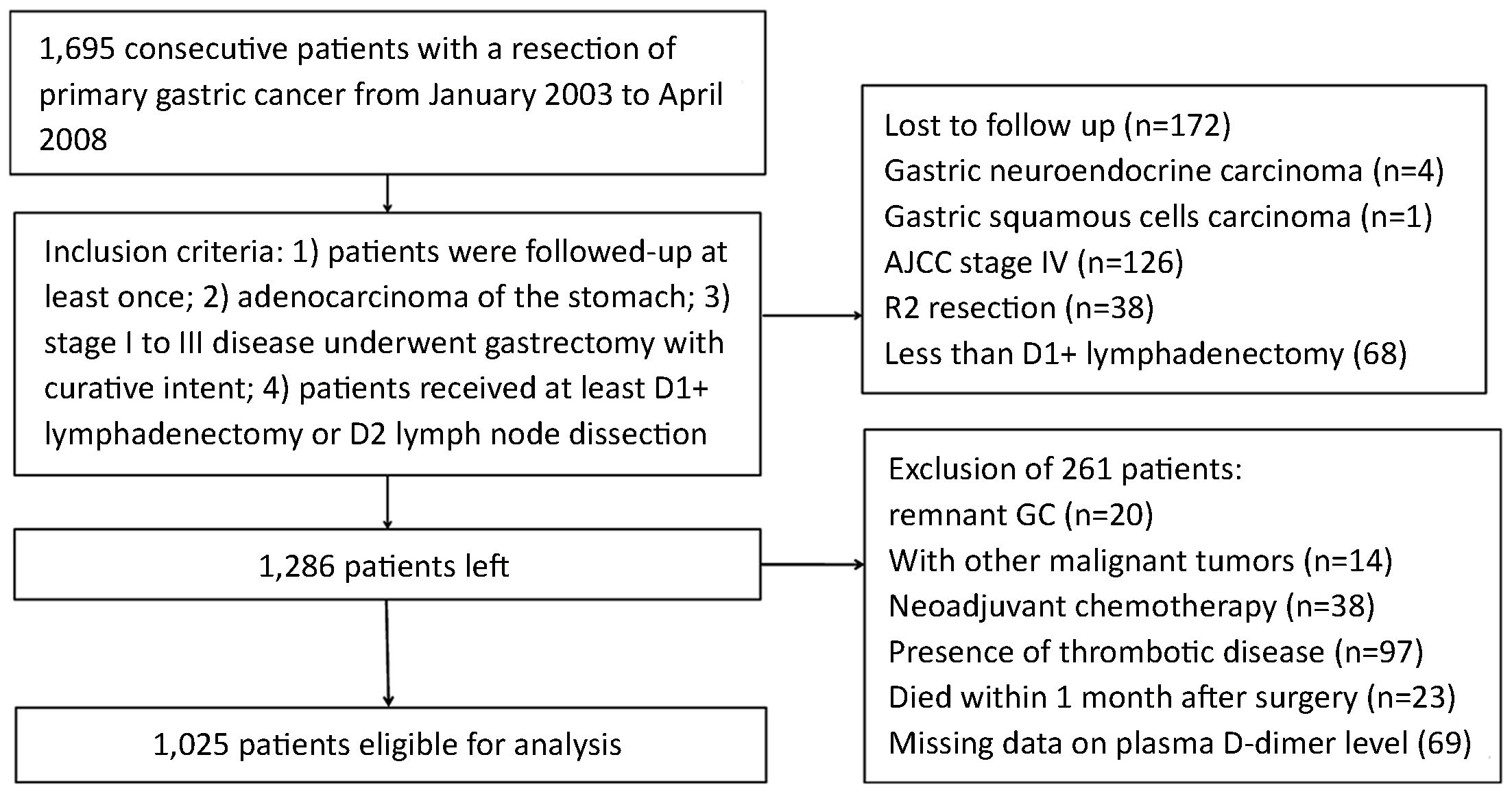

The Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute & Hospital has reviewed and approved this study. A total of 1,695 patients with GC who underwent surgical resection at Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute & Hospital between January 2003 and April 2008 were eligible for this study. Inclusion criteria for this study included: 1) patients were followed-up at least once; 2) adenocarcinoma of the stomach; 3) stage I to III disease underwent gastrectomy with curative intent; and 4) patients received at least D1+ lymphadenectomy or D2 lymph node dissection. And exclusion criteria were: 1) history of gastrectomy or other malignancy; 2) history of neoadjuvant chemotherapy; 3) presence of thrombotic diseases; 4) patients died during the initial hospital stay or for 1 month after surgery; or 5) missing data on PDL. After exclusion of 670 patients as shown in Figure 1, ultimately, a total of 1,025 patients were enrolled in this study.

Evaluation of clinicopathological variables and survival

Clinicopathological features studied included sex, age at surgery, body mass index (BMI), tumor location, tumor size, Borrmann type, histology, depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, postoperative chemotherapy, curability, lymph nodes retrieval and types of gastrectomy.

The tumors were staged according to the 7th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM Classification System, whereas lymphadenectomy and lymph node stations were defined according to the 3rd English Edition of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (16). Tumors were classified into two groups based on histology: differentiated type, including papillary, well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, and undifferentiated type, including poorly differentiated or undifferentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma and mucinous carcinoma.

Follow-up

The patients were followed-up by his attending physician and the research nurse of Department of Gastric Cancer, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute & Hospital. To increase the follow-up rate, methods such as telephone, message, correspondence and outpatient department visits were used together. The patients were followed up every 3 months up to 2 years after surgery, then every 6 months up to 5 years, and then every year or until death. Physical examination, laboratory test [including assessing carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), CA72-4, and CA242 levels], Chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasound (US) were performed at each visit, while endoscopy and abdominal computed tomography (CT) were obtained every 6 months. The overall survival (OS) rate was calculated from the day of surgery until time of death or final follow-up. The date of final follow-up was December 30, 2012.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, which were presented as x±s, parametric analysis was performed using Student’s t test. Categorical variables were analyzed by means of the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. OS curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method based on the length of time between primary surgical treatment and final follow-up or death. The log-rank test was used to assess statistical differences between curves. Independent prognostic factors were identified by the Cox proportional hazard regression model. To overcome bias due to the different distribution of covariates for the two groups, the propensity score analysis was used to obtain a one-to-one match by using the nearest-neighbor matching method. And we imposed a caliper of 0.25 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. Variables involved in the propensity model were sex, age at surgery, BMI, tumor location, tumor size, Borrmann type, histology, depth of invasion, N stage, TNM stage, postoperative chemotherapy, curability, average lymph nodes retrieval and types of gastrectomy. P<0.05 (bilateral) was considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical analysis program package IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22.0; IBM corp., New York, USA).

Results

Clinicopathological features and outcome of the whole study series before matching

Of the 1,695 patients, 89.9% (1,523/1,695) of the patients were followed up at least once. After excluding 670 patients, ultimately, 1,025 patients were included in the analysis and the median follow-up for the whole study series was 36 (range: 1–110) months. One thousand and twenty-five patients included 745 males (72.7%) and 280 females (27.3%). The age ranges from 20 to 89 years, and median age was 62 years. Of the 1,025 GC patients who underwent gastrectomy, 950 patients had a R0 resection, and 75 patients ended up with an R1 resection. Three hundred and fifty-six patients received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX6) or capecitabine and oxaliplatin (XELOX).

All the patients were categorized into two groups based on preoperative PDL: the elevated group (EG), patients with PDL >500 μg/L, including 163 patients; and the normal group (NG), patients with PDL ≤500 μg/L, including 862 patients. Clinicopathologic variables were compared between the two groups as shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences in sex, BMI, tumor location, Borrmann type, histology, curability, average lymph nodes retrieval and types of gastrectomy between the two groups, whereas patients in the EG were more likely to have a larger proportion of tumor size ≥5 cm (67.5% vs. 55.8%, P=0.006), elder mean age (64.0±10.8 years vs. 60.5±11.6 years, P<0.001) and advanced tumor (T), node (N), and TNM stage, but less likely to accept postoperative chemotherapy (27.6% vs. 36.1%, P=0.035) than in the NG.

Full table

In the entire study population, patients in the EG had a significantly lower OS rate than those in the NG (5-year OS rate: 27.0% vs. 42.6%, P<0.001) (Figure 2A). The results of the univariate and multivariate survival analysis are shown in Table 2. A total of ten factors evaluated in the univariate analysis had a significant effect on survival: age at surgery (<70 years vs. ≥70 years), tumor location, tumor size (<5 cm vs. ≥5 cm), Borrmann type (type III and IV), histology, TNM stage, curability, types of gastrectomy, postoperative chemotherapy and the PDL. In multivariate analysis, age (≥70 years), tumor size, Borrmann type (III and IV), TNM stage, curability and chemotherapy were found to be independent prognostic factors for OS, and the PDL was not a significant factor (hazard ratio was 1.13 for EG, P=0.236).

Full table

Patients characteristics and survival after propensity score matching

We analyzed 163 patients in each group, who were selected by one-to-one matching using propensity scores. The median follow-up was 23 (range: 1–103) months for the matched pair. Characteristics after the propensity score analysis are shown in the right columns of Table 1. One hundred sixty-three of the 862 patients in the NG were matched with 163 patients in the EG after covariate adjustment. The adjusted propensity score for patients with elevated PDL was approximately identical to that for patients with normal PDL (0.205±0.083 vs. 0.205±0.088, P=0.958). Figure 3 displays the distribution of the propensity scores in the matched and unmatched patients with elevated PDL and those with normal PDL. All covariates were equally distributed over the two matched groups. Matched patients in the EG had a similar sex ratio, mean age at surgery, BMI, tumor location, tumor size, Borrmann type, histology, depth of invasion, N stage, TNM stage, chemotherapy, curability, average lymph nodes retrieval and types of gastrectomy as those of the matched patients in the NG.

In the matched study series, the OS rate showed no significant difference between the EG and the NG. The 5-year OS rates were 27.0 % in the EG and 25.8% in the NG, respectively (P=0.809, log-rank) (Figure 2B).

Discussion

Cancer patients often demonstrate a hypercoagulable state, and previous studies have shown that an activation of the coagulation system plays a crucial role in tumor development, dissemination and metastasis (14,15,17,18). D-dimer, which is produced when cross-linked fibrin is degraded by plasmin-induced fibrinolytic activity, is a useful indicator for hyper-coagulation. Many studies have affirmed that cancer patients with high PDL were more likely to have poor prognosis and aggressive characteristics (2,5-15). To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first analysis using propensity score methods to assess the impact of preoperative PDL on outcomes for GC patients. Based on the patient characteristics, a strong imbalance in baseline characteristics between patients with elevated PDL and with normal PDL was identified. However, the negative impact of PDL on OS in the unadjusted analysis disappeared after risk adjustment in multivariate Cox regression and propensity score analysis. Therefore, elevated PDL did not contribute to the decreased survival; conversely, the clinical conditions of the patients led to the elevated PDL.

With regard to the prognostic impact of PDL, many studies have found that high levels of plasma D-dimer were associated with poor prognosis in several malignant diseases, including lung cancer, colorectal cancer, esophageal cancer and breast cancer (5-12). For example, Fukumoto et al. reported that the preoperative PDL was an independent prognostic factor in patients with completely resected NSCLC, and the OS rate was significantly decreased in patients with D-dimer >0.5 μg/mL ( 5). Oya et al. demonstrated that high preoperative PDL was associated with advanced tumor stage and short survival in patients with curatively resected colorectal cancer (9). As for GC, few studies focused on D-dimer. Liu et al. reported that the median OS was 48.10 months in patients with PDL less than 1.465 μg/mL and 22.39 months in patients with PDL exceeding 1.465 μg/mL, and PDL was identified an independent prognostic factor for GC patients in multivariate Cox regression analysis (13). They concluded that PDL might be a valuable biomarker for peritoneal dissemination and prognosis evaluation. Diao et al. founded D-dimer level was increased in patients with distant metastasis and especially hematogenous metastasis patients, and GC patients with high D-dimer level displayed early tumor recurrence and poor outcome (14). These studies draw the same conclusion that high level of plasma D-dimer had an adverse effect on OS for GC patients. However, these results were strongly biased due to the different baseline characteristics between patients with high PDL and with low PDL. These factors included depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, TNM stage, tumor size, age and cancer embolus, which had a significant impact on OS. To overcome bias due to the different distribution of covariates for analyzed groups, a one-to-one match was applied by using propensity score analysis in the present study. Before matching, we found that GC patients with elevated PDL demonstrated a significantly lower OS rate than those with normal (5-year OS rate: 27.0% vs. 42.6%, (P<0.001), which was consistent with previous studies. However, the survival difference lost significance when the baseline characteristics were optimally adjusted and balanced (5-year OS rate: 27.0% vs. 25.8%, P=0.809) and PDL was not an independent prognostic factor for OS in multivariate analysis. Therefore, a causal relationship between elevated PDL and worse outcomes does not exist. The poor outcome of GC patients with high D-dimer level was due to other reasons rather than the D-dimer itself.

The correlation between high PDL and poor prognosis is still unclear. Several studies confirmed that fibrinolytic activity which resulted in the generation of plasma D-dimer was up-regulated in patients with metastasis disease (19). Usually, the process of metastasis and tumor growth requires a number of steps to occur within a favorable host environment. Fibrin remodeling is involved in many steps of metastasis and has been proven to play a crucial role in the formation of new vessels (20,21). Fibrinogen-deficient mice have been shown to develop fewer metastases compared with mice with intact fibrinogen in a previous study, which revealed the importance of fibrin remodeling in tumor growth and metastasis (22). However, Fukumoto et al. deemed that the presence of circulation tumor cell or micrometastasis before treatment accounted for the poor survival as they found that NSCLC patients with high D-dimer levels had a higher incidence of postoperative recurrence (5). In the present study, patients with elevated PDL were more likely to have elder age at surgery, larger tumor size, advanced tumor (T) and node (N) stage. This was in accordance with a previous study conducted by Kwon et al. who demonstrated that D-dimer level was correlated with the depth of invasion, degree of lymph node involvement and tumor stage (2). Tumor depth and lymph node status are well-known prognostic factors, and patient age has also been reported to have an impact on the long-term outcome of GC patients (23-26). We think that it is the aggressive characteristics that contributed to the poor survival of GC patients and elevated preoperative PDL may provide valuable information for predicting the presence or degree of lymph node involvement and invasion depth.

Conclusions

Though GC patients with elevated PDL had a poorer prognosis than those with normal PDL, preoperative PDL was not an independent prognostic factor for GC patients after curative resection. It was the aggressive characteristics such as elder age, larger tumor size, advanced T, and N stage that contributed to the decreased survival of GC patients with elevated PDL rather than the PDL itself. The level of preoperative plasma D-dimer might provide supplementary information regarding disease status, including lymph node involvement and depth of invasion.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- Im JH, Fu W, Wang H, et al. Coagulation facilitates tumor cell spreading in the pulmonary vasculature during early metastatic colony formation. Cancer Res 2004;64:8613–9. [PubMed] DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2078

- Kwon HC, Oh SY, Lee S, et al. Plasma levels of prothrombin fragment F1+2, D-dimer and prothrombin time correlate with clinical stage and lymph node metastasis in operable gastric cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2008;38:2–7. [PubMed] DOI:10.1093/jjco/hym157

- Dupuy E, Hainaud P, Villemain A, et al. Tumoral angiogenesis and tissue factor expression during hepatocellular carcinoma progression in a transgenic mouse model. J Hepatol 2003;38:793–802. [PubMed]

- Buller HR, van Doormaal FF, van Sluis GL, et al. Cancer and thrombosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical presentations. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5(Suppl 1):246–54. [PubMed] DOI:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02497.x

- Fukumoto K, Taniguchi T, Usami N, et al. The preoperative plasma D-dimer level is an independent prognostic factor in patients with completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Surg Today 2015;45:63–7. [PubMed] DOI:10.1007/s00595-014-0894-4

- Zhang PP, Sun JW, Wang XY, et al. Preoperative plasma D-dimer levels predict survival in patients with operable non-small cell lung cancer independently of venous thromboembolism. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:951–6. [PubMed] DOI:10.1016/j.ejso.2013.06.008

- Kaseda K, Asakura K, Kazama A, et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative plasma D-dimer level in patients with surgically resected clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study. J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;12:102. [PubMed] DOI:10.1186/s13019-017-0676-3

- Kilic M, Yoldas O, Keskek M, et al. Prognostic value of plasma D-dimer levels in patients with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis 2008;10:238–41. [PubMed] DOI:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01374.x

- Oya M, Akiyama Y, Okuyama T, et al. High preoperative plasma D-dimer level is associated with advanced tumor stage and short survival after curative resection in patients with colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001;31:388–94. [PubMed] DOI:10.1093/jjco/hye075

- Lu SL, Ye ZH, Ling T, et al. High pretreatment plasma D-dimer predicts poor survival of colorectal cancer: insight from a meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget 2017;8:81186–94. [PubMed] DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.20919

- Diao D, Zhu K, Wang Z, et al. Prognostic value of the D-dimer test in oesophageal cancer during the perioperative period. J Surg Oncol 2013;108:34–41. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/jso.23339

- Batschauer AP, Figueiredo CP, Bueno EC, et al. D-dimer as a possible prognostic marker of operable hormone receptor-negative breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1267–72. [PubMed] DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdp474

- Liu L, Zhang X, Yan B, et al. Elevated plasma D-dimer levels correlate with long term survival of gastric cancer patients. PLoS One 2014;9:e90547. [PubMed] DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0090547

- Diao D, Wang Z, Cheng Y, et al. D-dimer: not just an indicator of venous thrombosis but a predictor of asymptomatic hematogenous metastasis in gastric cancer patients. PLoS One 2014;9:e101125. [PubMed] DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0101125

- Diao D, Cheng Y, Song Y, et al. D-dimer is an essential accompaniment of circulating tumor cells in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2017;17:56. [PubMed] DOI:10.1186/s12885-016-3043-1

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 2011;14:101–12. [PubMed] DOI:10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5

- Hong T, Shen D, Chen X, et al. Preoperative plasma fibrinogen, but not D-dimer might represent a prognostic factor in non-metastatic colorectal cancer: A prospective cohort study. Cancer Biomark 2017;19:103–111. [PubMed] DOI:10.3233/CBM-160510

- Jiang HG, Li J, Shi SB, et al. Value of fibrinogen and D-dimer in predicting recurrence and metastasis after radical surgery for non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol 2014;31:22. [PubMed] DOI:10.1007/s12032-014-0022-8

- Blackwell K, Hurwitz H, Liebérman G, et al. Circulating D-dimer levels are better predictors of overall survival and disease progression than carcinoembryonic antigen levels in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2004;101:77–82. [PubMed] DOI:10.1002/cncr.20336

- Chiarug V, Ruggiero M, Magnelli L. Angiogenesis and the unique nature of tumor matrix. Mol Biotechnol 2002;21:85–90. [PubMed] DOI:10.1385/MB:21:1:085

- Wojtukiewicz MZ, Zimnoch L, Jaromin J, et al. Immunohistochemical demonstration of fibrin II in gastric cancer tissue. Pol J Pharmacol 1996;48:229–32. [PubMed]

- Palumbo JS, Potter JM, Kaplan LS, et al. Spontaneous hematogenous and lymphatic metastasis, but not primary tumor growth or angiogenesis, is diminished in fibrinogen-deficient mice. Cancer Res 2002;62:6966–72. [PubMed]

- Isobe Y, Nashimoto A, Akazawa K, et al. Gastric cancer treatment in Japan: 2008 annual report of the JGCA nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer 2011;14:301–16. [PubMed] DOI:10.1007/s10120-011-0085-6

- Liang YX, Deng JY, Guo HH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of gastric cancer in patients aged ≥70 years. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:6568–78. [PubMed] DOI:10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6568

- Liang H, Deng J. Evaluation of rational extent lymphadenectomy for local advanced gastric cancer. Chin J Cancer Res 2016;28:397–403. [PubMed] DOI:10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2016.04.02

- Di Leo A, Marrelli D, Roviello F, et al. Lymph node involvement in gastric cancer for different tumor sites and T stage: Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (IRGGC) experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1146–53. [PubMed] DOI:10.1007/s11605-006-0062-2